Wet · lands

New York City – “the urban jungle”, is a place better known for its rising glass shards and boulevards of concrete, steel girders swinging from crane-tops hundreds of feet over our heads, pavement filled with cars and buses zooming their way between the buildings, subways grinding against steel rails beneath our feet. Yet scattered throughout the boroughs are natural habitats that we can get lost in - many different types of ecosystems competing for and sharing resources. Among these are the densely forested trails of Alley Pond and Van Cortlandt Park, the meadows and ponds of Central and Prospect Park, the waterways of Jamaica Bay and Pelham Bay – and soon to be the newest addition to New York’s vast park system – Freshkills Park and its 360 acres of wetlands.

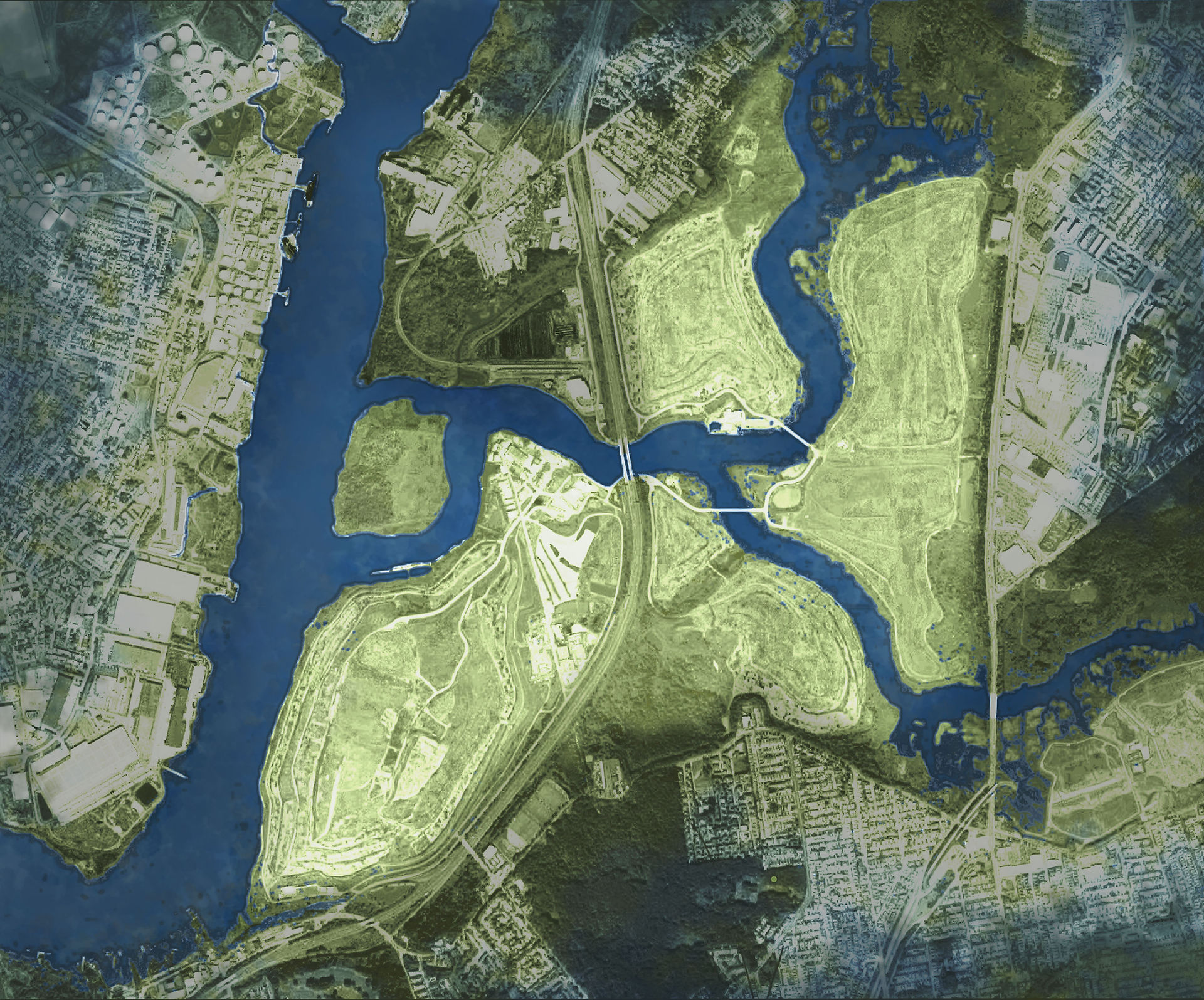

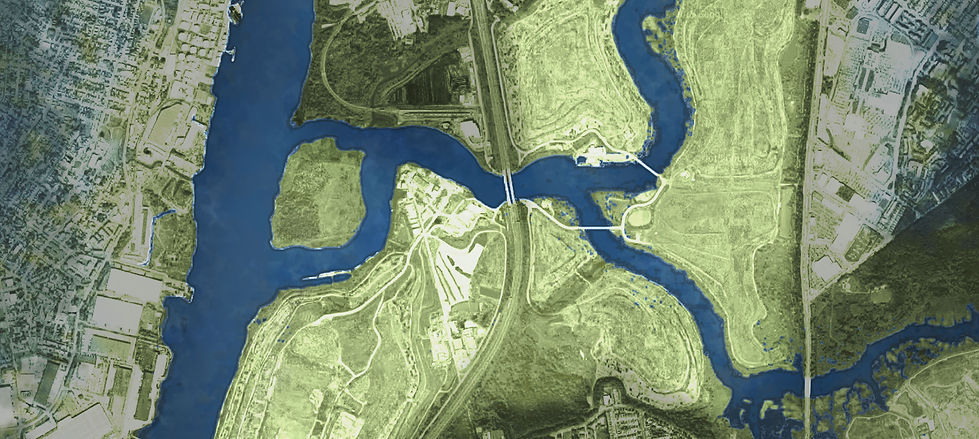

Freshkills Park is located at the confluence of two tidal creeks on the western shore of Staten Island. For decades it was the site of Fresh Kills Landfill, one of the biggest landfills in the world, within New York City's borders. The soft sands along these shores produce a wetland – an environment variably saturated by the tide that obscures the boundary between land and water. It is an ecosystem that is nurtured by semidiurnal tides whose twice daily fluctuations transform the landscape -

HIGH TIDE CONSUMES THE EDGES, WIDENS THE CREEK AND BRINGS THE WAVING STANDS OF REEDS TO THE WATER LINE. LOW TIDE EXPOSES THE NUTRIENT-RICH MUD AS THE CREEK SHRINKS AWAY, LEAVING BEHIND RIVULETS MEANDERING THROUGH THE SEDIMENT.

Wetlands are a critical piece of environmental infrastructure. As a habitat, wetlands support a diverse ecosystem of plants and animals, fish and birds that rely on the fluctuating water levels, wet and dry conditions and the flow and distribution of nutrients available in the water and the soil.

Remarkably, wetlands are also important to the development of cities and the preservation of coastlines. They are a natural buffer between open water and solid ground. The soil and plants that line the water’s edge filter sediment and pollutants that may be found in the water. They also absorb the impact – the speed and force – of tides and waves that land on the shore. During Superstorm Sandy in October 2012, the wetlands and mounds of what will soon be Freshkills Park absorbed and contained the influx of water that entered the creeks of the park and helped protect the surrounding residential neighborhoods from suffering the kind of flood damage experienced by residents in other parts of Staten Island's low-lying communities.

Recognizing the importance of wetlands, both as natural habitats and as urban infrastructure, has helped contribute to their stewardship. This is a sweeping change of perspective to the one that had actually created the Fresh Kills Landfill in the first place. Generally, the approach towards wetlands was to fill them or contain the water flow to make better use of land that was considered wasteland. The Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn is a good example of this policy as well. What was once part of a natural tidal marsh near Red Hook was contained with concrete bulkheads along which different types of industry was able to develop and use the confined waterways for transportation. The decision, made and carried out by Robert Moses in 1948, to build a temporary municipal landfill on the salt marsh along Arthur Kill in Staten Island fell in stride with the sentiment of times. The temporary status was extended indefinitely as the landfill became a much needed, albeit provisional, solution for the garbage produced by a growing city.

But change was coming as the environmental protection movement gained momentum in the latter part of the 20th century. The final call was to cease landfill operations by the end of 2001, a decision much supported by the Staten Island residents and visitors who were living under the oppressive smells of rotting garbage in the landfill nearby. North, South and East Mound had already been capped in 1996 and 1997 and West Mound is currently being capped as of this writing [2015]. The capping process is a means of isolating the decomposing garbage from making its way into adjacent waterways or from leaching into the soil. This containment operation is critical to maintaining a safe environment for future park goers and revitalizing habitat.

Just as with any ecosystem, there is a balance among the organisms that live off the nutrients within it; this balance is indicative of its health and resilience. Throughout the park, researchers are collecting data and monitoring the park’s progress as it recovers from decades of landfill operations. These same researchers are also performing interventions - planting, seeding, weeding - that help facilitate this process.

In my brief internship with Freshkills Park in the summer of 2015, I was able to glance at the efforts being made to re-establish this space as a habitat and natural park for New York City. The Freshkills Park Alliance, in collaboration with researchers and universities, have been reintroducing native plants and wildlife into the habitat, in an effort to build up the resilience of the ecosystem. The teams are practicing new techniques to assess the diversity of wildlife as well as observing how their interventions are contributing to the revitalization. The park itself is a fascinating integration of natural habitat and urban infrastructure operating within the same space. Wild in some places and highly constrained in others, it is very representative of New York’s tenuous relationship between centuries of development stacked on top of such lush and diverse ecosystems.

On a typical scheduled trip into the park a caravan of cars full of researchers, students, volunteers and their sundry equipment gather at the entrance to be led by the Freshkills Park Alliance staff to a test site along one of their creeks on which their research is based.

After passing through the park’s secured gates, our jeep travels along a paved road often traversed by Department of Sanitation vehicles that are still operating on the site. The route through Freshkills Park first takes us past DSNY’s Transfer Station where NYC’s garbage is collected and then loaded onto barges to travel to other landfills; a little ways down the road, under an overpass and over a bridge, we pass North Park’s Flare Station, a facility that serves as a safety measure to monitor methane emissions of the decomposing garbage sequestered under what now appear to be rolling hills full of lush vegetation.

After a few minutes we turn onto a gravel path that trails alongside one of the creeks. The jeep heaves over bumps along the way lifting clouds of dust as it brushes past fanning stacks of Phragmites Australis - an invasive reed that towers over other plants. This reed is a powerful presence in the park. It lines this road, among many others that rise from the softer, muddy soils along the creeks. These dense stands are topped with deep purple plumes, rising way over our heads to ten feet in height. As beautiful as they are in this landscape, they create a negative impact on wetland restoration. This species is considered invasive because it takes over an ecosystem by starving other plants of nutrients and creating a monoculture of plant-life that also narrows down the diversity wildlife that is able to survive in the area. Part of the struggle with reintroducing native plant life is battling this particular reed which has a complex system of underground stems known as rhizomes that feed many stands in one area. The rhizomes have a form of reproduction that make it very difficult to eradicate and efforts to remove the plant from an area often involve extreme measures such as slashing and burning over the course of many years. Testing the health of a wetland also means scanning it for biodiversity and the level of invasive plant species present and dominant.

Aside from the rustling of the wheels along the surface of the road and the distant creak of the suspension, Fresh Kills Park is eerily quiet. Birds chirp and flutter, insects buzz and the wind whishes by occasionally. The sound of the city is a faint hum produced by a distant highway hidden behind mounds and tall grasses. The tops of buildings and distant bridges are hazy just above the horizon.

In reality, these mounds are part of the engineered infrastructure that isolate the landfill waste. There, under layers of impermeable plastic and soil, the biological process within the garbage takes over, until it is completely decomposed and becomes inert. This process is called capping, and provides for the safe extraction of the byproducts of decomposition - mainly methane and leachate. Various systems, both hidden underground and sometimes emerging from the mounds, operate to safely move these byproducts to their treatment stations. The methane is used as a source of energy for many Staten Island homes. The leachate is treated and released into the sewage system.

Throughout the lush green mounds, along the roads that encircle the park, metal pipes peek out from the brush. They are a feature of the flare stations and landfill infrastructure that pop up throughout the park – a reminder that, as easy as it is to get lost in the beauty of the wildness here, everything we encounter here is part of a much bigger operation. In a strange way, as alien as these gas vents seem scattered throughout undulating hills and meadows, they appear here like wildlife, heads bent grazing in open fields.

The jeep comes to a halt at a brief and subtle break in the reeds. The team disembarks, unloads its cargo, and gears up for a trek into the reeds which leads to the muddy and drenched soils of the wetland shoreline. In waterproof waders we part the dense stands of reeds and carve a path toward the creek’s elusive edge. Step by the step the firm ground beneath our feet gets spongier until the growths of Spartina Alterniflora, a native wetland grass, come to an abrupt halt along the edges of a mudflat.

The mudflat is the so-called no man’s land between the creek and the firm ground. It is the area that alternates in saturation as the tides pull in and out of Freshkills Park. On morning visits, the creek is midway between low and high tide and slowly the mudflat is growing in length, taking over more and more of the surface from which the water recedes. The edges along Freshkills’ shores are difficult to pinpoint. They move with the tides - a vertical change of approximately five feet, four times within a 24 hour cycle - submerging and revealing up to 100 lateral feet of spongy mud.

The mud acts like quicksand, standing in one place for too long or one misstep and you can end up knee deep in the ground. The more experienced researchers embrace the challenge, having learned how to handle such a predicament, though much of the team proved to be more on the cautious side, staying along the reeds where the ground is firmer.

The researchers and their team make observations, collect samples and map the points where each was taken. Each visit is an opportunity to observe the vibrancy of this ecosystem. The wildlife that crawls, wriggles, nestles, and scampers is ever-present to the keen observer. Freshkills, and the shoreline specifically, is teeming with life.

GAS VENTS SEEM SCATTERED THROUGHOUT THE UNDULATING HILLS, A FEATURE OF THE LANDFILL INFRASTRUCTURE AND A REMINDER OF THE SITE'S HISTORY

A CREEK AND DSNY FACILITIES ARE SEEN IN THE BACKGROUND FROM THE ROAD

CARVING THROUGH THE REEDS TO REACH THE MUDFLATS

A DSNY FLARE STATION IS SEEN FROM THE ROAD

Debris still accumulates along the shoreline. Whether it was blown off the mounds years ago or washed up through the tidal creeks is unclear. Some of the refuse has been there long enough to cultivate several habitats, particularly along North Park. The ecosystem is taking over and each season brings Freshkills closer to its natural state. It may never return to its original state but as it moves further from its past as one of the largest landfills in the United States, its place in our collective memory can shift from one of a nuisance to a real public good. Its artificial mounds, created by decades of trash collection, will now irreversibly be a part of its identity. The collaboration of researchers and the Freshkills Park Alliance - and many others like it - help protect this public asset and provide a home for New York City’s wildlife and place of respite from urban life for its residents.

WATER TESTING ALONG THE CREEK

RETURNING WITH SAMPLES IN HAND